Formal Language Structure to Describe a Universal Theory of Everything

Yoshixi

Motivation

I take notes. I love taking notes. I love organizing notes. I use obsidian to organize my notes. Anyone that knows me knows me for my depravity in taking notes on things.

Part of my note taking process involves categorizing relations of notes such that they are easy to find and organized in a natural and justified manner. I spend a long time organizing things. I don't know the optimal method on how to structure a note. I don't know how the note contents should be laid out, and how it should be evalauted at a meta-level in its relationship to other notes. What I do know is that certain approaches I take to document mathematical concepts differ wildly from how I should document the edge-case-heavy nature of linguistic concepts, or the ambiguous parts of philosophical ideas.

Ive been motivated to find out if there is some formal method we can use to encapsulate information. If there is a structure we can use to describe concepts about everything in the universe. If a system like this indeed exists, then we have a method to convert everything known, like articles on wikipedia, or perhaps any document on the internet into a formal structure to be slotted into our massive vault of concepts to have documentation about everything in the world. Indeed, I find myself cross referencing other sites like wikipedia or books to extract definitions and theories to add to my current vault. And for no other reason than to just make my vault contain as much information as it can. Its hoarding. We all love to hoard...

I wonder what gems we can find if everything is related. I find myself thinking about how beneficial to humanity a centralized knowledgebase is. The main benefit of such a thing, is the ability to create a Unified Theory of Everthing

Universal Theory of Everything

Ok, so what exactly is a universal theory of everything? From my understanding, it is something that can be used to explain everything that exists in this world. Every physical property, every phenomenal property. It can explain any theory that we may have. It feeds into the theory of relativity, quantum mechanics, electromagnetism in some way. It is linked to all concepts in some way.

An example of a theory of everything is:

String Theory:

Everything is a collection of one-dimensional strings that vibrate at different rates.

This concept of string theory in isolation cannot describe everything, but the derivative concepts it describes can be used to describe everything. i.e: string describe particles, particles form to create atoms that form to create matter that form to create all material constructs that form to create psychological phenomena, etc...

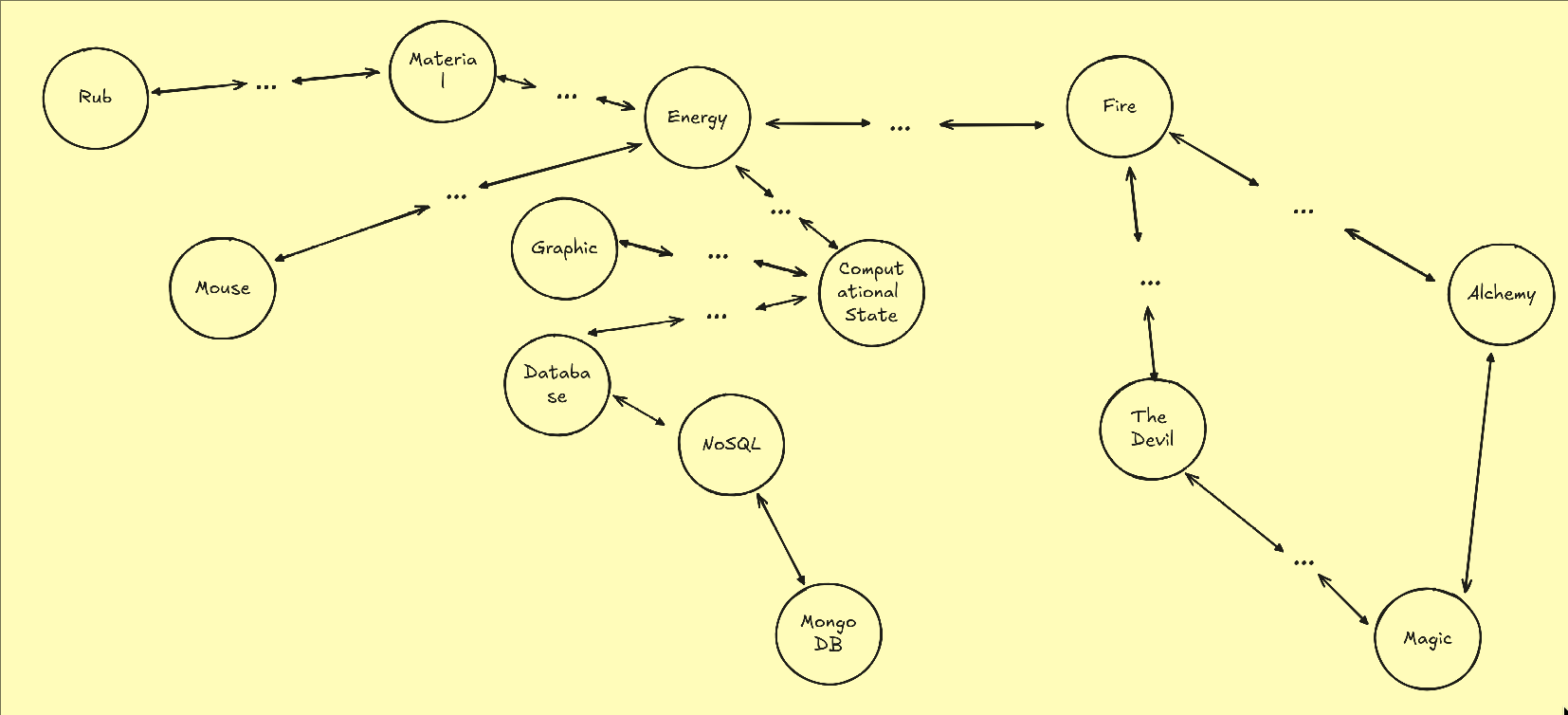

If we take this at a higher approach though, what we find is that the requirement for a theory of everything just requires a concept that is linked in some relation to every other concept.

In a graph where everything is connected to everything else, simply pick a random node and base your theory off that. Eventually, you will be able to explain everything else in relation to your original node.

Obviously, there are more thing to consider that make a good theory of everything. Ideas like how coherent the theory is.

But yes, once we connect everything, this is what we can make.

In a graph where everything is connected to everything else, simply pick a random node and base your theory off that. Eventually, you will be able to explain everything else in relation to your original node.

Obviously, there are more thing to consider that make a good theory of everything. Ideas like how coherent the theory is.

But yes, once we connect everything, this is what we can make.

Calculus of Construction

Ive been intensely captivated to learn what CoC (Calculus of Construction) is and how information can be used to create formal documents. Formal verification is one of those things you hear about as a reverse engineering, but never get too deep into it because its so mathematically heavy. Many formal verification tools are provided and used by reverse engineers - most notably SAT solvers. There are languages like F*, Metamath, LEAN and Rocq that exist to prove mathematical statements. A collection of these proofs can be found online: (https://madiot.fr/rocq100/). Segments of proofs can be used in other proofs.

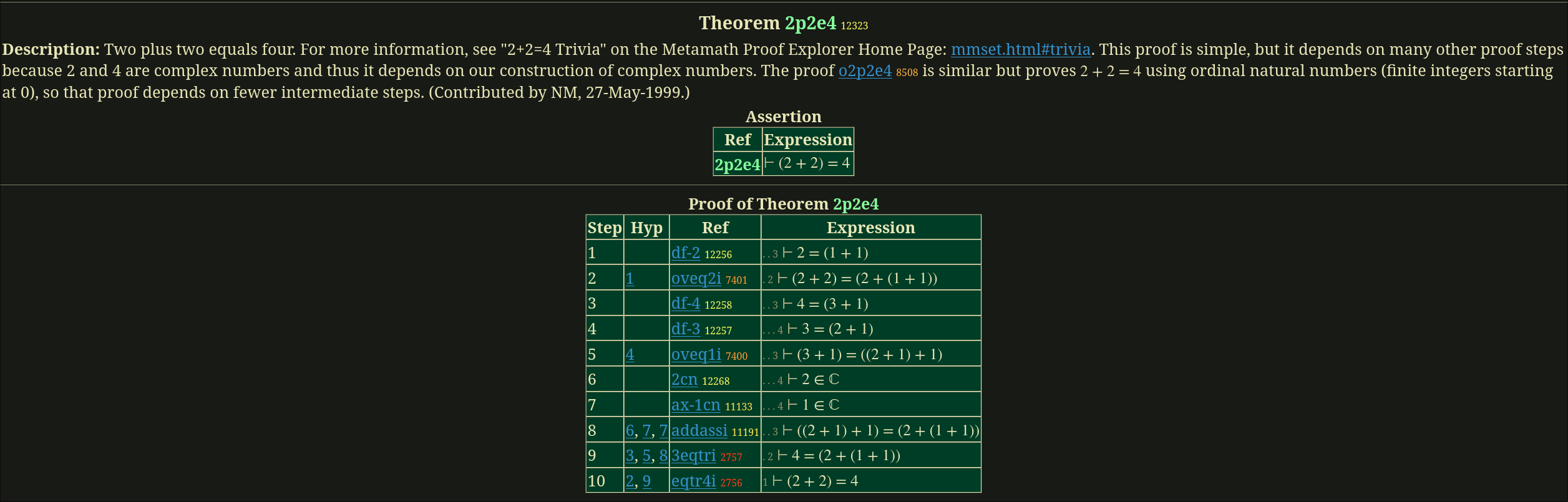

Anyhow, a year ago while I was doing calculus 1, I encountered the Metamath proof explorer site. Here was a site that documented many mathematical theorems and tied them together with links to other theorems or axioms. https://us.metamath.org/mpeuni/mmtheorems.html#dtl:1.1.

Most documents have a brief structure like:

# Theorem

# Assertion Syntax

# Proof of Theorem

Or if its an axiom:

# Axiom

# Assertion Syntax

This is a proof that two plus two equals four. You can view the proof [here]

Anyways, this was partially the inspiration for what we wanted.

Formal Language Proposal

To allow things to depend on other things and concepts, we can define each concept as a file structured like such:

// Imports

// Types

// Export/Definition

- The import field is whatever notes we are importing from other notes

- The type field is whatever properties this concept has, that are defined by some other note

- The export section is whatever the definition of the concept is - logically defined from whatever you imported. You can export either a Type or a Function

This language is based off functional programming. Everything is a function.

Lets try and define some concept - Ice and this is how it would look:

// Imports

import /Philosophy/Philosophy_of_Science/Physics/Thermodynamics/State_of_Matter/Solid

import /Philosophy/Philosophy_of_Science/Physics/Electromagnetism/Light/Color/Colorless

import /Philosophy/Philosophy_of_Science/Physics/Thermodynamics/Matter_Transitions/Freeze

import /Philosophy/Philosophy_of_Science/Physics/Thermodynamics/Matter_Transitions/Freeze/Frozen

import /Philosophy/Philosophy_of_Science/Chemistry/Chemicals/Water

// Types

- Solid

- Colorless

- Frozen

// Exports/Definition

Ice : Freeze(Water) // we are exporting as a type here

Note: maybe we can use namespaces here aswell haha

Addressing Problem of Definitions

In western linguistics, there are different methods of language:

- Statements (What is)

- Imperatives/Commands (What should be done)

- Questions (What is not known)

An example of each is:

- Statement: The day is sunny

- Imperative: Go dry the clothes!

- Question: What are clothes?

The way we structure our language, definitions are by default statements. We do not have a clean way to establish concepts that have definitions that are imperatives or questions.

At first glance, we could perhaps create a function like Imperative() or Question() to convert our standard definition into a imperative and question. However, it is not exactly a smooth transition.

Take for example: the statement The mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell.

We could perhaps convert it to a question like: The mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell? But what would this exactly be asking? Would we be asking people to verify that the mitochondria is indeed the powerhouse? I guess it would be fine, but it isn't structured like how a good question would be.

The main issue lies in converting this statement into a command. The mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell!. Usually commands are done to call you to action, but what sort of action does this command lead to?

Well, there is an answer for the command part. Philosophers say that when we utter commands like It is wrong to kill! (which is structured like a statement), what we actually convey is a call to action to want people to follow this statement. So when we say, The mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell!, we do have a call to action, and that call to action is for people to believe this fact.

This is not the best way of side-stepping this problem, but I think its fine for now.

Addressing Double Definition Problem

This is a problem when the definition of a concept is not agreed on. If there are multiple definitions, then which one do we select to use to define this concept?

Many people debate the definition of identity. Some theories believe:

- Identity is based off your physical body

- Identity is based off your physical brain

- Identity is a collection of the memories you have

- Identity is based off your 'soul' We need a way to account for all these different definitions without making our organizational system too complex.

We can solve this by borrowing a concept from functional programming - the idea of a type class. A type class allows multiple types to be representative of a shared type such that they can be used interchangably. This is the whole idea of using a type field in the first place. We define the original concept to be something trivial, and create subconcepts that have the type of the original concept. :)

Addressing Double Group Problem

How can we decide how to organize things? Certain concepts may occur as part of different hierarchies. For example, consider the concept: Windows 11.

We could have a structure be like:

/Philosophy/Political_Philosophy/Economics/Business/Microsoft/Products/Windows11

or alternatively a structure like:

/Philosophy/Technological_Philosophy/Software/Operating_Systems/Commercial_Operating_Systems/Windows11

What we can do is setup both of these to point to the same note - kind of like a symbolic link.

I guess in this case, we would represent each of these levels like a node in a graph aswell.

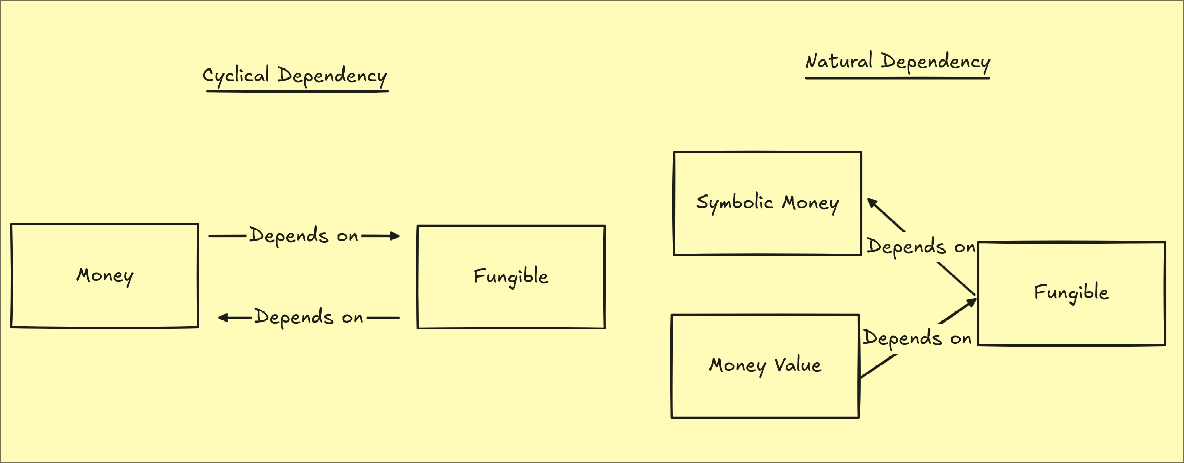

Addressing Cyclical Dependency Problem

What if we have two concepts that depend on eachother for their definition? Lets consider the definitions of Money and Fungible. Money is something that is fungible (can be traded). Fungible is a tool with (monetary) value. Both definitions depend on eachother, but this is actually a non-problem.

You may have already realized that the value of money and the concrete 'tradable' money we are talking about are different things. Money is comprised both its value and its symbolic token (whether it be a physical coin or digital representation).

So, if we want to make this concept less-cyclical, then we split money into both its valuable concept and symbolic concept.

So, if we want to make this concept less-cyclical, then we split money into both its valuable concept and symbolic concept.

Capturing concepts

Now that we have this logic system in place, how can we capture the definitions for each of these scenarios?

I watched this video by a fear and hunger youtuber that was a whole lore dump, but they brought up an idea from ancient philosophy called the platonic form.

A platonic form is the idealized version of a concept. It is the ideal version of school, the ideal version of marriage, the ideal version of love, etc. It is what plato believes help us capture real knowledge. The catch is that - we as normal people don't have this full platonic form as our understanding. Nobody knows what true love is. No, rather we have only a segment of the form rather than the entire form. We all have different segments of this ideal form.

The idea is that the more views we get, the closer we get to the real form. So, it follows that if we want the real concept, we gather as many variations of this concept that are published online and find the resulting similarities.

So, TLDR: scrape the entire internet for all definitons, and then summarize with a LLM haha.

Different Logic Systems

Ok, so heres the thing. This system is biased obviously to western understanding of logic (analytical philosophy). What if our logic is not suited to describe everything?

This is indeed a very involved problem. We want to describe Everything. Not just the english side of the internet, we want to cater to everything in the world, possibly even different logic systems we don't even know about...

This is something i have no answer to, i dont even know how to reason if its not analytically. Perhaps meaning is conveyed through the creative side of your brain (right side i think?) and we can distribute concepts with picturs?